Reducing Student Anonymity and Increasing Engagement

Katherine J. Kuchenbecker

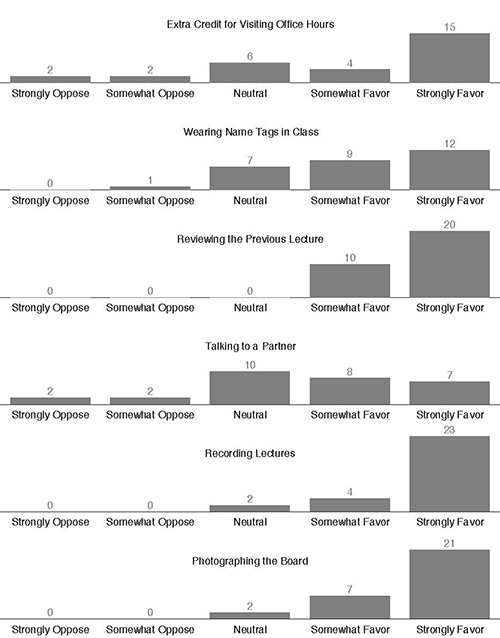

When I was a sophomore in college, I had to take a lecture course that was required for my major but that didn’t particularly interest me. The professor was enthusiastic and experienced, but class met at 10 a.m. (early!), and I was one of about one hundred students. I hated the experience of falling asleep in lecture, and I knew I wouldn’t be missed if I stayed in bed or worked in the machine shop instead of going to class. Now as a faculty member here at Penn, I have taught a comparable course for the last six spring semesters—MEAM 211: Dynamics. Over my first few years of lecturing, low attendance showed that many of my students were skipping class, so I started changing small aspects of my teaching to see if I could help them get more out of my lectures. Specifically, I sought ways to reduce student anonymity, make my lectures more coherent and engaging, and enable students to learn from my lectures after class. After several years of experimentation and refinement, I settled on the six ideas described below. As shown in Fig. 1, an anonymous online survey yielded feedback on these ideas from 30 of the 93 students whom I taught in spring 2015.

To make my students feel less anonymous, I offer one extra credit point for visiting my office hours (OH) during the first four weeks of the semester. More than half the class typically stops by, giving me the chance to start learning their preferred names and where they’re from. Most survey respondents favored this idea, commenting that the extra credit helped them overcome their shyness and that visiting once made it easier to visit OH later, when they needed it. Students also liked knowing that their professor wanted to get to know them. Two students opposed this idea because they had conflicts during all of my OH. Another good suggestion was to offer extra credit for visiting the TA office hours.

I also combat anonymity by having each student wear a clip-on name tag showing his or her preferred name during the first four weeks of lecture and recitation. Made during the first class, these name tags enable me to call on a wide range of individuals and practice names learned in OH. Students can stop wearing their name tag when they think I know their name, and I am not ashamed of occasionally messing up or asking for a hint. Respondents largely favored this idea, commenting that they really liked having a professor use their names. Students also appreciated learning the names of their classmates. On the negative side, a few students found bringing their name tag annoying, and another felt awkward wearing theirs when others did not.

To increase coherence and engagement, I start every lecture with a five-minute summary of the previous class. Supported by just one projected slide, I emphasize the important concepts, formulas and examples from the last class, building a natural bridge into upcoming topics. All 30 respondents either somewhat favored or strongly favored this idea—a very strong showing of support! Enthusiastic comments noted that these reviews helped them get into the mindset of the course, making it easier to learn new material. A few students wished my review slides were more organized. One student mentioned these reviews made them feel it was acceptable to arrive late to lecture, and another suggested including an important (ungraded) question to make the reviews more interactive.

I also seek to make lectures more engaging by having students talk about a tricky question with a partner, usually twice per class. After a few minutes I lead the class in discussing the question, calling on various student teams to share their thoughts. This idea received the most mixed ratings, with approximately half favorable and most of the rest neutral. Respondents who favored this idea commented that talking with a partner helped them develop their own intuition for the material and let them brainstorm new solutions before being told the answer. Others said that these discussions provide a nice break in lecture, although several mentioned that I sometimes gave them too much time for the discussion. Students who opposed this idea preferred to sit alone in class, found it difficult to find a partner for the discussion or felt the discussions were ineffective.

To enable access to my lectures after class, I use Penn’s lecture recording system. It automatically captures and posts online what I show on the projector and what I say into a wireless lapel microphone. Over several years, I moved most of my instructional materials into computer-based media so they could be recorded. Personally, I find that being recorded improves my focus, and listening to a few recordings helped me understand how I sound to the students. Students overwhelmingly favor the use of the lecture recording system, stating that it helped them stay caught up with the course when they were sick, had to travel or slept through lecture. Supporters also mentioned that the recordings were useful for reviewing confusing topics and studying for exams. The only two students who were neutral about lecture recordings never used them. One student recommended improving the recording frame rate to better handle movies and simulations.

Finally, drawing diagrams and solving problems by hand are important skills in my discipline, but the current lecture recording system cannot capture what one writes on the board. Thus, I photograph all of the chalkboards at the end of every lecture, and I insert these photographs into my slides before posting them online. This simple step takes just a few minutes and beneficially gives me a perfect record of what I wrote on the board for next year. Students overwhelmingly favor this practice, saying it was extremely helpful to see what I had written when listening to the lecture recording. Others mentioned that the photographs helped them study for exams. A few students mentioned that my board work was sometimes hard to follow, and others would prefer a hand-written solution captured by the lecture recording system or simply posted online afterward.

These six ideas are just a few of the many adjustments I have explored to increase the effectiveness of my lectures. As you can see from the student ratings and comments, they succeed to varying degrees, and there are many ways in which they could be improved. I value this continual process of small innovations, student feedback, refinements and more small innovations because it matches the ever-changing tide of students while keeping me engaged in teaching a subject that I first learned about when I was just a sophomore in college.

Katherine J. Kuchenbecker is the Class of 1940 Bicentennial Term Chair and associate professor of mechanical engineering and applied mechanics in the School of Engineering and Applied Science; she received a 2014 Lindback Award for Distinguished Teaching.

This essay continues the series that began in the fall of 1994 as the joint creation of the College of Arts and Sciences, the Center for Teaching and Learning and the Lindback Society for Distinguished Teaching.

See https://almanac.upenn.edu/talk-about-teaching-and-learning-archive for previous essays.