Understanding What Students Get Out of Your Class

With the increasing evidence supporting structured, active, in-class learning (SAIL), I set out to convert my sophomore level biomechanics course, BE200, to a SAIL format in the fall of 2014. As I spent hours developing new material, struggling with the best way to implement this structure, I wondered if the conversion was really going to be better for my students. How was I going to tell if this worked? What did I actually want my students to get out of this experience? Grades certainly aren’t the only metric of learning, but what does learning really mean? And once I figured out what was important, how was I going to tell if my students accomplished those things?

Assessment can mean many different things in the classroom—verbal and written exams, group work and papers to name a few. The gold standard tends to be final grades, but I was hesitant to rely solely on a metric that can vary so much from semester to semester. I also knew that many factors go into obtaining a high grade in a course, including exam anxiety, time management and math errors in problem solving, unrelated to a student’s actual grasp of the material. After much thought, I decided to focus on two specific areas connected to the goals of my course: increasing students’ conceptual understanding and increasing students’ confidence in their skills. The first was an attempt to decouple learning from the other factors that can influence grades. The second stemmed from my desire to better understand the self-perceived learning of my students. How would they describe their abilities when they entered the course, and how did they change as the semester progressed? I would consider a successful class one in which students became more confident over the course of the semester, even if those feelings fluctuated during the term as they struggled with new or difficult topics.

To assess conceptual understanding, I drew from previously published concept inventories—assessments common in math and physics. These inventories focus on the concepts behind mathematical and engineering theories rather than the numbers or “correct” solution. Questions are more general and have multiple choice answers with formats such as “expect an increase” or “A will move faster than B” and are presented in both words and graphical form. The published inventories formed the basis of my assessment, and to fill in any gaps, I created course questions in a similar style. These concept questions were administered at the beginning and end of the semester to track student conceptual gains in both the SAIL version and the previous year’s lecture-only version. While not graded, students were required to complete the assessments for participation ensuring a near-complete student sampling. Material was divided into prerequisite material and new biomechanics material. The prerequisite material included topics from math and physics that my biomechanics course would build directly upon—material that the students should have already learned. New biomechanics material tested conceptual knowledge of topics they’d learn over the course of the semester. I didn’t expect them to know the mathematical reasoning behind any of these solutions, but since it was a conceptual assessment in a course driven by physical phenomenon, I was interested in knowing what their “gut” told them.

At the end of the course, students showed increased gains in biomechanics course material in the SAIL formatted class compared to the traditional, lecture-only format. As a baseline assessment, this was an encouraging result. However, this increase was not noted in the prerequisite material. Though improved understanding of the prerequisite material was not an explicit course objective, these ideas were reinforced throughout the semester as the concepts were applied to biomechanics examples and problems. Perhaps this simply means the SAIL format isn’t changing how students apply concepts from other courses, but considering that the scores were far from 100%, it made me realize that these connections are not as clear to the students as I think they should be. This was also a result that would have been difficult to observe in grades alone. Because prerequisite material is buried within the course material, my traditional homework and exams may never have picked up on this trend if I had not implemented this type of assessment.

To better understand the self-perceived learning of my students, a completely different type of assessment was needed. I wanted to know if the types of activities we were utilizing in the SAIL course increased student confidence or if the required interactions in the student group work stressing them further. Surveys were given at the beginning and end of the semester inquiring about students’ confidence in their skills. Questions in multiple choice and short answer format covered topics such as group work, applying concepts to their other math and science courses, enjoyment in learning biomechanics and problem solving skills to name a few.

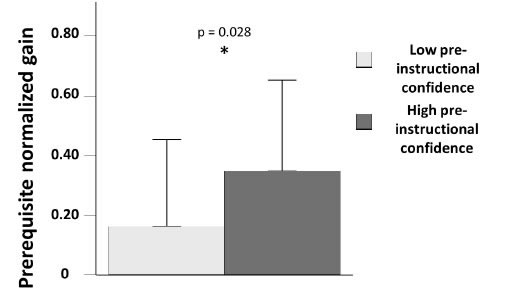

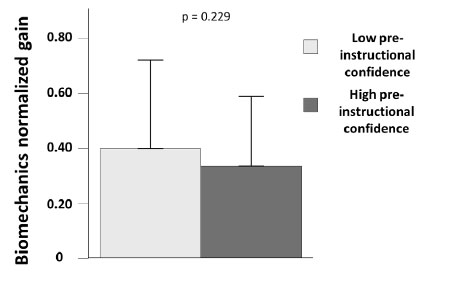

Over the course of the semester, students’ confidence levels in both problem solving skills and group work grew. However, the most interesting finding was how these changes in confidence related to their conceptual gains on the concept assessments. Students entering the course were clustered into two groups based on pre-instructional confidence in problem-solving related skills: the low pre-instructional confidence group and the high pre-instructional confidence group. As may be expected, students in the low pre-instructional confidence group showed significantly lower prerequisite conceptual gains over the course of the semester. These results suggest that students with low confidence, perhaps as a result of previous experiences with learning math and physics, may have a disadvantage when it comes to learning new related material. However, and perhaps most importantly, students in the low pre-instructional confidence cluster showed equal biomechanics conceptual gains compared to their peers, suggesting that this barrier can be overcome. Unfortunately, these positive conceptual gains did not translate into higher grades; students that entered the course with low confidence tended to receive lower grades than their peers.

The disconnect between grades, confidence and conceptual understanding is still unclear to me but has made me slowly rethink the things I emphasize on assignments used to determine grades. For example, conceptual questions and big picture problem solving outlines have made their way onto my exams and homework. The one thing I do know is that without the incorporation of assessments outside of my normal toolbox, I’ll never be able to fully understand my students’ learning process and the impact of my teaching on it.

Low pre-instructional confidence showed fewer prerequisite material gains. |

Low pre-instructional confidence showed similar biomechanics conceptual gains. |

LeAnn Dourte is a senior lecturer in bioengineering in the School of Engineering and Applied Science.

In 2015 she was awarded the Hatfield Award for Excellence in Teaching in the Lecturer and Practice Professor Track.

In 2016 she received the American Society of Engineering Education (ASEE) Biomedical Engineering Teaching Award.

_____________________________

This essay continues the series that began in the fall of 1994 as the joint creation of the

College of Arts and Sciences, the Center for Teaching and Learning and the Lindback Society for Distinguished Teaching. See https://almanac.upenn.edu/talk-about-teaching-and-learning-archive for previous essays.