Research & Innovation

As on-campus research resumes, bringing research back online is not as simple as picking things up where they were left in the spring. It requires strategic planning, flexibility, and an understanding that shutdowns and travel restrictions are beyond the control of researchers and will likely have lasting impacts on their work.

Field Surveys on Hold

Paul Schmidt and his lab are interested in how insect populations adapt to seasonal weather patterns and climate change. The group regularly samples fruit flies, both at nearby sites in rural Pennsylvania as well as from international locations and has also been running a mesocosm experiment at Pennovation Works since 2014. Because the work is inherently seasonal, Dr. Schmidt says it’s possible that they could lose an entire calendar year’s worth of work. While the group hopes to run a reduced version of the experiment over the summer to maintain continuity, resuming field work won’t be easy. In Pennsylvania, Dr. Schmidt typically reaches out to owners of organic, pick-your-own orchards to get permission to sample. “You rely on that personal interface with people, and I don’t know what these places are going to look like now,” he said. “Research-wise, that’s going to be the biggest thing for us: navigating all these modifications and what the new normal is going to look like.”

Katie Barott’s work on coral reef resilience includes both lab experiments and fieldwork in Hawaii. Each summer, her group travels to the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology. Coral spawning events only occur during full moons in the months of June and July, so there is only a narrow window to collect data. When they miss it, they have to wait a whole year. Her team also had the opportunity last fall to collect samples during a coral bleaching event. They were hoping to track the reef’s recovery over time to learn how heat stress impacts coral reproduction, but now they will be missing several crucial time points. For Dr. Barott, it’s both disappointing and a missed scientific opportunity for a climate-change driven event.

Collaborations Face Delays

Many experimental physics and astronomical observatories work on a large scale. Because these projects are interwoven with numerous collaborators and institutions worldwide, delays to a single component can have a huge impact.

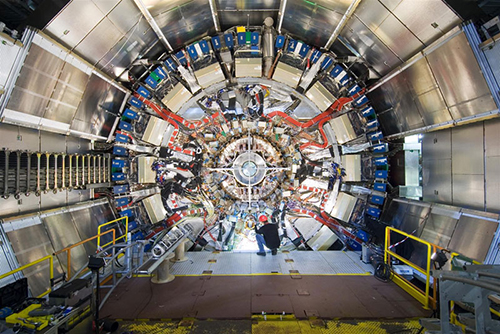

I. Joseph Kroll, Elliot Lipeles, Evelyn Thomson, and Hugh Williams are collaborators on ATLAS, one of two general purpose experiments at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), a 27 kilometer-long particle accelerator at CERN. Penn researchers play a crucial role in the maintenance and operation of a key component of the ATLAS detector known as the Transition Radiation Tracker (TRT). This shutdown period is an important time for key maintenance and upgrades, and being unable to work in the lab or to send their team members to CERN has been challenging.

“Being onsite and having experience working with the TRT is important for knowledge transfer, and that’s not possible right now,” said Dr. Kroll. “The science is going to get done, it just might take longer than anticipated.”

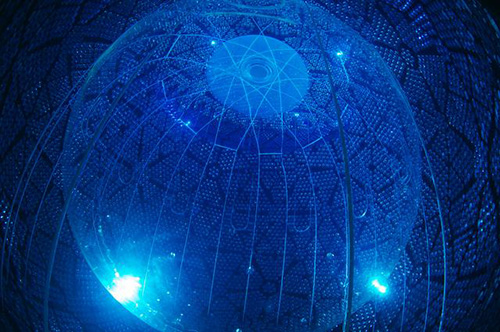

Joshua Klein and his group are part of the SNO+ collaboration, which studies subatomic particles called neutrinos at an underground facility called SNOLAB. Right before SNOLAB was shut down, the team was in the middle of filling the 40-foot wide acrylic vessel with 800 tons of scintillator. Now, it’s likely that, between the shutdown and the time required to get things running again, the project will face up to a six-month delay.

Dr. Klein and Chris Mauger also work on projects at Fermilab, a particle physics and accelerator laboratory near Chicago. With a skeleton crew in place, active equipment could be rebooted as needed, but work by outside researchers had to be halted. The group was able to shift its focus to design and data analysis, but Dr. Klein noted that “now we’re getting to that point where we’re really going to need people physically in the lab.”

Since 2016, Mark Devlin has been leading efforts to build the Simons Observatory, a $40 million astronomy facility in Northern Chile. A massive collaborative effort involving research groups from around the world, Dr. Devlin’s group is responsible for assembling the largest cryogenic camera ever built. Dr. Devlin’s group shifted to advanced project planning and were able to get hundreds of parts designed and manufactured. “We had a whole Gantt chart of things to do up through the end of the year, and we moved a lot of those forward,” he explained. “We’re ready to hit the ground running when things turn back on.” Still, Simons Observatory’s timeline still faces major delays because so many components from across the world have to be interface. “Everybody impacts everybody else, and the chain is only as strong as its weakest link.”

With tractors, earth movers, and cement trucks in place at the site in March, the shutdown was also an abrupt shock to the observatory’s construction. The extreme weather in this region could cause further delays.

Archaeological Conservation on Pause

Brian Rose at the Penn Museum has been leading efforts to excavate and conserve Gordion, the ancient capital of Phrygia in west central Turkey. Now with the travel restrictions, his group’s research efforts are likely to be set back by a full year. “As long as it’s only set back by a year, it’s not the end of the world, but you never know what’s going to happen,” said Dr. Rose.

Adapting and Accepting Uncertainty

As an experimental biologist, Dr. Schmidt understands the frustrations of losing momentum and is working with group members to develop detailed plans and realistic goals for the coming months.

Dr. Devlin is also no stranger to the frustration of lost momentum: The Balloon-borne Large Aperture Submillimeter Telescope (BLAST) project had major delays due to equipment malfunctions and bad weather. His advice is to “Just roll with it.” “If you sweat all that small stuff, you can’t make progress. You can sit there and work nine times as hard and get 10% done, or you can say that it won’t all get done but I’ll be in better shape when this all opens up,” he said.

Dr. Klein, as both the PI of his group and as the graduate chair of the department of physics and astronomy, is proud of how students have adapted—whether it’s taking materials to work on at home or learning new skills. “I tell the students that it’s OK to find yourself doing nothing because you have to process all of this. At the same time, it’s good to find things that you otherwise might not get time to do,” said Dr. Klein.

Dr. Rose’s first summer in Turkey took place during the 1980 military coup, and he and his team were also working at Gordion during the attempted coup in July of 2016. These situations showed him the importance of being adaptable.

Dr. Barott, despite her group’s disappointments in missing out on field work, is encouraged to see the lab maintain a sense of community, with virtual tea times and celebrating awards received by her group members. She tells her group members to work on maintaining a sense of purpose and to keep moving forward. “We’re at the whim of the world.”

—Adapted from a June 16, 2020, story by Erica K. Brockmeier in Penn Today. Read the full text at https://tinyurl.com/pennresearchincovid