Detecting Signals from the Early Universe

Penn astronomers are part of an international collaboration to construct the Simons Observatory, a new telescope that will search the skies in a quest to learn more about the formation of the universe.

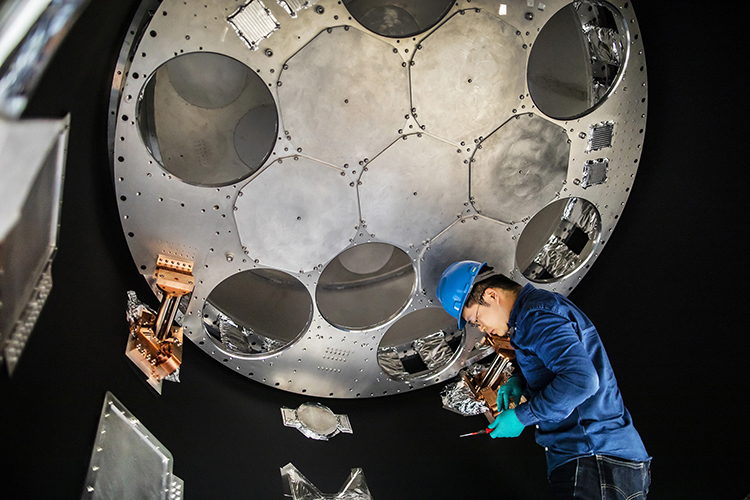

In early July of this year, a large aperture telescope receiver (LATR)—seven-feet wide and 8,000 pounds—was transported from Boston to Penn’s David Rittenhouse Laboratory and placed in the High Bay Lab, where the researchers on the team of Mark Devlin, the Reese W. Flower Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics in the department of physics and astronomy in the School of Arts and Sciences, were ready to get to work.

As members of the Simons Observatory collaboration, Dr. Devlin’s team will be putting the finishing touches on the LATR, the sensor that will be the “heart” of a cutting-edge astronomical observatory. The observatory will include a series of telescopes, located in the high Atacama Desert in northern Chile, that are designed to detect cosmic microwave background (CMB), residual radiation left behind by the Big Bang that astronomers study to learn about the first moments of the universe.

The challenge with measuring the CMB is that the signal is incredibly faint. “Because it’s so faint, we need to control the noise,” explained Zhilei Xu, a postdoc in the Devlin group. “And all of the electronics work better when they are colder. If it’s too hot, they are noisier.”

The CMB exists around three degrees Kelvin, nearly -450 degrees Fahrenheit. And because the Simons Observatory wants to study the CMB in the ultra-microwave range, they’ll need to make the detector even colder, down to 0.1 degrees Kelvin (0 Kelvin is Absolute zero, the lowest theoretical temperature that isn’t actually possible to reach).

As experts in cryogenics, the Devlin group is working on creating the right type of super-cold environment for the detectors to find the CMB. The group designed the massive metallic shell that will house all of the detection technology, with graduate students Ningfeng Zhu and Jack Orlowski-Scherer heavily involved in the design of the LATR.

Dr. Devlin’s team will spend the coming months running tests to make sure the LATR, the shell of which was fabricated in Boston with all components precise to one mm, works as it should before installing insulation, detectors, thermometers and sensors.

In parallel, the large aperture telescope, LAT for short, is being produced in Germany with the aim of having both the LATR and LAT assembled and shipped to Chile in early 2021. The goal is for the observatory to collect its “first light” sometime in the spring of 2021.

This is the largest ground-based CMB experiment ever built, and Dr. Devlin said that the finished product will be 10 times more sensitive than any other CMB experiment he’s worked on.

For the complete story, visit https://penntoday.upenn.edu/news/search-signals-early-universe