| Talk About Teaching And Learning |

|

, |

|

Relevancy, Organization and Passion in Teaching

Thomas A.V. Cassel

I am one of a few Full Practice Professors within the Associated Faculty at Penn. Among the qualifications for this untenured, five-year renewable appointment are “a high level of educational achievement and relevant practice experience.” Prior to accepting SEAS Dean Eduardo Glandt’s offer to launch Penn’s Engineering Entrepreneurship Program in 1999, my “relevant practice experience” was gained over 20 years as the founder and leader of a pioneering venture in the then-nascent independent electric power industry. It was a challenging, often turbulent, and ultimately successful journey. Much of the experiential knowledge acquired during that journey has, I believe, contributed to my apparent success in the classroom in terms of both the substance and delivery of course content.

In preparing to write this article, I spoke with course graduates and reviewed an eight-year stack of course evaluation forms. Evident from my students’ comments is a recurring appreciation for a course’s relevancy, organization and passion.

Relevancy. Consistent with Ben Franklin’s vision for Penn as a school in which students would learn “everything that is useful and everything that is ornamental,” a frequent comment from students in both my engineering entrepreneurship and economics classes relates to their perception of the courses’ relevance. They remark about concepts, skills and knowledge that are “useful” and “applicable in real world situations” at a professional level, and about “using lessons learned in all aspects of life” at a personal level. A student who graduated seven years ago writes, “So many of the concepts and ideas that I learned in class have manifest themselves on a professional level throughout my experiences at work. But so many more have crystallized in my everyday life.”

Related to my students’ (and Dr. Franklin’s) appreciation for relevance, is an article published last spring by Augier and March1 which addresses relevance in terms of experiential knowledge and in terms of academic knowledge. The article speaks of an enduring tension in engineering, business, law and other professional schools between experiential knowledge and academic knowledge. I have been party to a number of discussions at Penn about these two points of view. Experiential knowledge, as described by Augier and March, is “derived from practical experience in the field, stored in the wisdom of experienced practitioners and communicated by them. Its hallmark is direct and immediate relevance to practice.” Academic knowledge, on the other hand, is “derived from scholarship. It is stored in the theories of academics and is communicated by them. Its hallmarks are an abstraction from practice, which it looks to improve not so much through diffusion of ‘best practice’ as through changes in fundamental knowledge.” Advocates of academic knowledge see the immediate relevance of experiential knowledge as being limiting and myopic. Notwithstanding this century-old dispute, Augier and March’s research ultimately finds little or no dissent among scholars and practitioners alike from the desirability to integrate the two.

Though my appointment would appear to lean decidedly toward the relevance of practice experience, the construction of my courses seeks to integrate experiential and academic knowledge. Indeed the two complement each other. Homework assignments and classroom content typically examine a pertinent analytical model or concept drawn from scholarly journals, and then apply this academic knowledge to an experiential case study. Classroom choreography intertwines both lecture format and a Socratic approach to catalyze student participation in discussions. As one student commented, “Opportunities to voice an opinion encouraged me to think in class instead of being a passive note-taker.” Students also enjoy the color of an occasional anecdotal sidebar drawn from my personal “real world” experience in the trenches of entrepreneurial warfare.

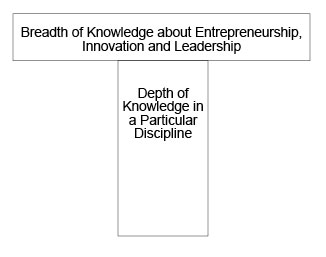

Our engineering entrepreneurship courses are often viewed as a capstone to an engineering degree. As illustrated by Byers2 , this complementary relationship resembles a “T” in which the depth of theoretical knowledge acquired in a major discipline underpins the breadth of knowledge— experiential and academic—in our entrepreneurship courses. The goal of such courses is to prepare students to seize an entrepreneurial opportunity rooted in their technological expertise.

Organization. Just as teachers recognize students’ preparation for each class, students recognize a teacher’s efforts to organize a course and plan each class. Prior to launching our first entrepreneurship course in 1999, months were devoted to curriculum development. A number of Penn’s peer institutions (e.g., Stanford, Cornell and Princeton) had recently initiated similar courses in their engineering schools. Student response had been overwhelmingly positive. Interviews with faculty at these schools and at Penn provided suggestions regarding content and methods of delivery. More suggestions came from practitioners in the venture capital, entrepreneurial and legal professions. Hours were spent studying case method pedagogy, and then interviewing and observing seasoned faculty at Penn and Harvard. The resulting product, which remains a work in progress eight years later, receives high ratings from Penn students. My colleague Jeffrey Babin, a fellow engineering entrepreneurship instructor, and I continually look to update this product by exploring journals, newspapers and on-line repositories, by comparing notes with other faculty, and by seeking ideas from practitioners. The interest taken, and the time and energy spent, in organizing the course are apparent to our students. This, in turn, motivates them to fulfill their part of the contract and prepare diligently for each class session. As in a company environment, this culture trickles down from leadership example and defines the norms of appropriate behavior by all parties involved in the course.

Passion. Teaching at Penn is an honor and a privilege.The opportunity to work with faculty colleagues and students at this exceptional university is energizing. Having a passionate attitude toward the teaching role, as well as toward the material being taught, is, no doubt, a common trait shared by all effective teachers. This interest and passion is quickly recognized by the students, and it is infectious. Students remark that “enthusiasm is clearly evident in lectures” which, in turn, “stimulates student interest” and “makes a significant difference in the experience.” Experiential and academic sources concur that a leader’s passion attracts and inspires others to follow. Passion is an intrinsic motivator for success. Students want to learn, not so much for the extrinsic purpose of a grade, but to satisfy an inner enthusiasm for knowledge. This infectiousness of passion begins with the instructor and becomes ingrained in the culture of the course.

Perceptions of relevancy, organization and passion are important to our students. When embraced by the teacher, these cultural elements appear to contribute to an effective and stimulating classroom environment. Of course, none of this apparent success would be possible without the support of a visionary dean, suggestions from faculty colleagues and practitioners, and assistance from staff and a cadre of exceptional TAs and graders. My thanks to each of you.

1 M. Augier and J.G. March, “The Pursuit of Relevance in Management

Education,” California Management Review, 49/3 (Spring 2007): 129-146.

_____________________

Dr. Thomas A.V. Cassel is a Practice Professor in the School of Engineering and Applied Science.

He is the 2007 Provost’s Award winner, the 2003 recipient of the S. Reid Warren, Jr. Award for Outstanding Professor and

Intellectual Mentor in SEAS, and the 2007 Ford Motor Company Award winner for faculty advising in SEAS.

This essay continues the series that began in the fall of 1994 as the joint creation of the

College of Arts and Sciences and the Lindback Society for Distinguished Teaching.

See www.upenn.edu/almanac/teach/teachall.html for the previous essays.

|